Staring at an ATM machine that is unable to dispense money or visiting a hospital for an operation only for it to be cancelled may have been scenarios in a Hollywood movie depicting the most dramatic of cyber attacks in the past.

Today, however, that was what some Ukrainians found when they tried to withdraw money from their banks. ATM machines were locked out by the latest global cyber attack and they had to borrow money from relatives and friends.

In the United States, hospitals were hit as well by the fast-spreading malware, leaving patients scheduled for operations waiting until the computer systems could be restored.

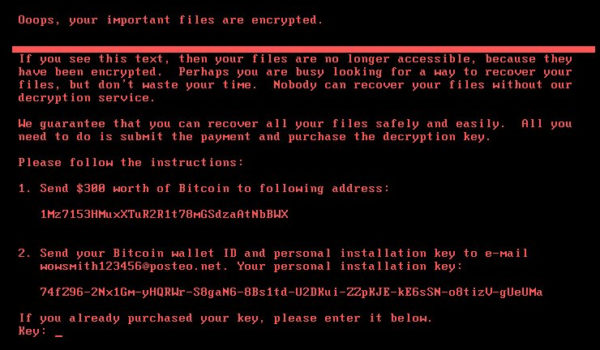

The latest online threat today is based on a piece of ransomware called Petya, which tells victims to pay up US$300 in digital currency to unlock their machines.

That’s a suspiciously small amount, so some industry experts are saying it may be a cover for targeting a specific victim and stealing information on the quiet while everyone is rushing to fix this urgent issue.

Whatever the real motivation, the effect it has had on everyday life is indisputable. Coming just weeks after similar WannaCry ransomware attacks, this cyber infection spreading uncontrollably across the globe is the latest warning that the consequences of such attacks have escalated dramatically.

From a Russian bank that was left paralysed to an Australian factory for the Cadbury chocolate brand being forced to halt production, the victims suffered from temporary disruption to serious worries about lost data and even nuclear fallout.

At the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine, workers were forced to manually monitor radiation when their computers failed, The New York Times reported.

Just days ago, in a separate attack on the British parliament, hackers compromised up to 90 e-mail accounts before being contained. The country’s defence secretary has since threatened military strikes against such attackers.

And let’s not forget that the latest malware attack used the same hacking tool that the US National Security Agency developed. When this so-called Ethernal Blue tool was leaked, it became something that could be traded online.

Entire ransomware systems are set up today to not only hawk malware but to identify victims’ locations and send the ransom note in their language. Those from wealthier countries are naturally of higher priority among a pool of compromised machines, according to security companies familiar with the threat.

In other words, someone with access and means can sign up for a “ransomware as a service”, much like buying software or music on demand, to deploy it around the world.

That points to one worrying conclusion: In the arms race today, the defenders appear behind the curve against increasingly well-organised and sophisticated hackers.

It shows when even a known threat can wreak such havoc. Based on a Windows loophole that was patched by Microsoft back in March, Petya and WannaCry can be stopped if users are more vigilant or organised.

Unfortunately, in an interconnected world of machines that are not always well maintained, the task is not as easy as it sounds.

And what of the “zero-day” exploits that even Microsoft and others have no clue about but which have been developed by governments as secret cyber weapons? There’s good reason to fear the unknown.

Indeed, there aren’t any surefire defences that users can rely on, except to make themselves less of an easy target. Or to prepare for an attack so as to recover more quickly from it.