The concept isn’t new. Indeed, flashing one’s phone to pay for a burger, cuppa or train ticket is something that has been around for years. Even in Singapore, where trials were carried out extensively in the past.

Yet, the hype is all about China’s mobile payment today. With either WeChat Pay or AliPay, from the country’s two big Internet companies, you can scan a bar code with your phone to pay for anything from a hotpot meal to groceries.

How easy is it? I tried things out with a WeChat Pay account I set up on a trip to China this week. It’s easy because it’s so widely accepted and the technology is mature over years of use and refinement.

WeChat is as common as WhatsApp in Singapore, so any of the nearly 1 billion WeChat users in China can potentially use it to pay for things or transfer money to friends.

All I had to do was set up a WeChat account, then link it to a bank account or credit card number. Now, I don’t have a Chinese bank account, so I scanned my Singapore credit card. It worked – sort of.

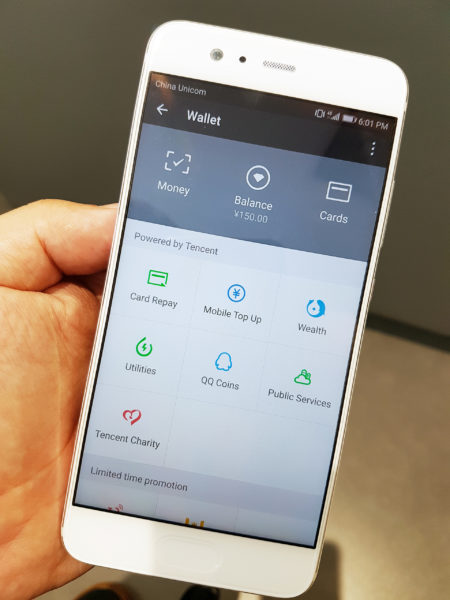

Before I can go shopping, I still needed to top up the phone wallet with virtual cash. So, the folks from Huawei, who lent us a P10 phone to try this out with, sent a token 150 yuan (S$30) to my WeChat account via what’s called a hongbao.

It’s as easy as sending a message on WeChat. And yes, you can send the virtual money any day, not just during Chinese New Year.

With that, I paid for a burger and meal at McDonald’s by simply using the phone to scan the barcode at a self-service machine.

I had to have the app ready to get this done, but I didn’t get my hands dirty with any cash. Before I left China, I returned the balance to a Huawei representative by sending her a hongbao back.

How different is this from what Singapore already has? Well, very little in the way of features.

With Apple Pay, Samsung Pay or Android Pay, you can simply tap a phone on a reader at the cashier and pay through a linked credit card. Out in Singapore since last year, these methods are actually more secure because you authenticate the transaction with your fingerprint.

So, why is China hailed as a leader in mobile payment? One reason is because of the sheer size of the market and the number of users already on such payment services. Even beggars have been known to ask passers-by to scan a bar code to give them money.

What’s not said as often is how integrated these mobile wallets are with the messaging apps as well as other services, such as taxi booking and food delivery. On a single screen on WeChat, you can send messages as easily as money. Plus pay for all sorts of on-demand services.

Indeed, that’s the real story behind China’s success. None of the payment apps here have the same sort of integration. DBS’ PayLah is a great app that lets you transfer money to someone via a phone number, but it’s not part of, say, WhatsApp or Grab.

Of late, there have been some efforts to develop this concept of an app within an app. GoJek, a popular app in Indonesia that was originally made for hailing a bike ride, now lets you book a massage and seek a cleaner as well.

Yet, all this wonder and amazement at China’s systems needs some qualification. The country has outlawed many Internet services, from Google to WhatsApp, thus allowing only a couple of homegrown companies to flourish without international competition.

Even though popular phone models from Huawei, Xiaomi and Oppo run Android in China, they don’t have a Google Play Store out of the box to easily download apps, like the rest of the world.

Instead, many apps are available, say, via a Huawei app store or apps within WeChat. This means users find it easier to go with one app to do everything, rather than seek out various different ones.

Can Singapore import the technology and business model, as Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong suggested during his visit to Beijing this week?

Already, WeChat and Alipay are available in Singapore, but anecdotal evidence suggests they are usually used by Chinese tourists more familiar with them.

Singapore is different in many ways. WhatsApp is more popular here, not WeChat or AliPay. Plus, there isn’t the same worry about counterfeit notes as in China, which is one reason why people prefer to go cashless.

Singapore, of course, can take a leaf out of China’s book. For starters, take a global model, copy it, then refine it for local use. With so many mobile payment services already available, there’s no need to rush to reinvent the wheel here.

The more important task is to make things easy for users. Forcing users to adopt a cashless system, as the transport system is being primed for by 2020, is one way to get people to use the technology.

But that can only go so far. Notice how stored value cards such as ez-link and CashCard have found it so hard to go beyond non-transport uses. They have to make sense to people, by being easier and possibly cheaper to use. And yes, more places need to accept them.

That’s probably the most important lesson from China – users determine the success of a system. Simply importing the same technology here won’t work.

If users are happy with tapping a contactless credit card or a phone on a screen, instead of scanning a barcode, what’s wrong with that?