Welcome to the future, a friend told me after I finally used my phone as a virtual ez-link card today to tap myself through the fare gate at an MRT station.

I had bought a new phone a couple of days ago and switched to a new NFC (near-field communications) SIM card at my telecom operator. The reason: my old SIM card had got stuck in the broken SIM card tray in my old phone.

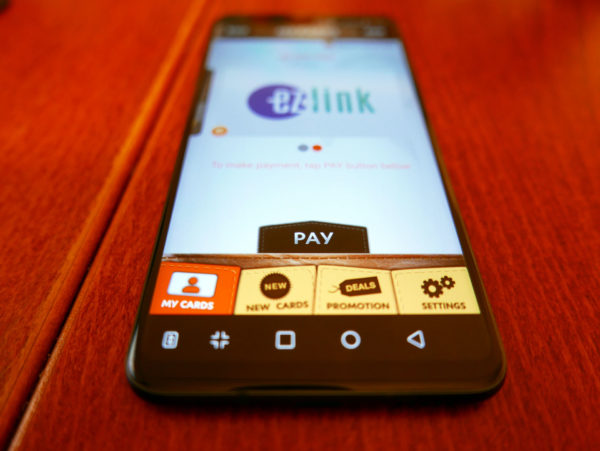

With that in place, I can basically use the phone the way I would an ez-link card or NFC-enabled credit card. The first thing I did today was to top up this virtual wallet.

The way to do it – and no one tells you this at the telco or an MRT station – is to place your phone on the top-up machine and treat it like a card.

A few seconds later, I had S$10 on my virtual ez-link card. It helped to see this on the rather rudimentary interface on the M1 NFC Services app that came with my phone (there’s an M1 Mobile Wallet app you have to download separately).

Still a little worried but excited, I proceeded to the nearest gate at City Hall station. I picked a section that wasn’t crowded.

First tap – nothing. After several tries, panic set in and I was ready to take out my real ez-link card. Then I turned my LG V30+ around. It worked! The green icon came up and the gate opened. My first train ride paid with my phone.

Except it wasn’t. More than 10 years ago, I had already tested a similar technology while a reporter at The Straits Times. Back then, the phone was a mere prototype made in small amounts and not sold to the public.

That worked as a concept but it would take until 2016 for phones sporting NFC SIM cards to be introduced for transit use in Singapore. In 2018, I finally got on the cashless bandwagon when it came to paying for a ride with a phone.

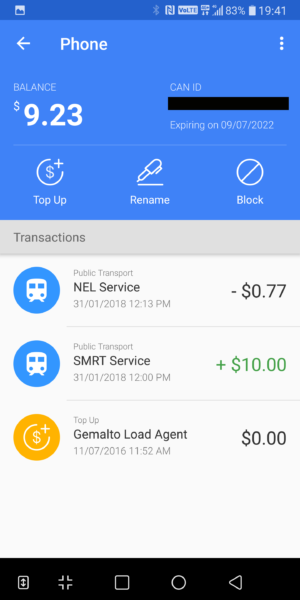

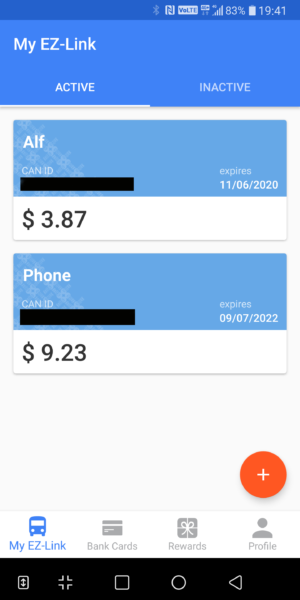

What’s so cool about it? For starters, I can see all the transactions I have made on my app. Besides the M1 wallet app, you can also download the EZ-Link app to do this.

This isn’t the most intuitive at first – I had to key in the ez-link ID on my phone manually and the information wasn’t updated instantaneously – but it works mostly.

More importantly, I could top up the ez-link card by adding a credit card to the account. So, no more getting stuck at the top-up machine or running out of value, as I do sometimes.

Of course, the downside is that your phone has to be powered on for things to work. If you run out of battery, it’s back to the good old ez-link card.

And if you watch too much Netflix on the train, and the juice runs out before you tap out at your destination, you’re stuck. Approach the train station manager, please.

Why jump through all these loops? As another friend mentioned, it might be easier to tape an ez-link card to the back of your phone and enjoy “cashless” convenience.

He’s kidding, of course, but in terms of reliability, you can probably count on the card more today, though it isn’t as powerful as a phone wallet.

Certainly, my experience reflects what many users face when it comes to cashless payment in Singapore. It is not easy enough to use because not enough effort has been spent educating users about these options.

Could top-up machines at the stations have instructions to top up a phone and not just a card, for example? After all, these NFC SIM card phones have been compatible for a couple of years now.

Perhaps the bigger bugbear is cost. M1 charges S$37.45 for a new NFC SIM, which is similar to a new SIM card, but then adds a S$9.10 NFC activation fee to the bill. It’s as if you’re being punished for trying out the new technology.

StarHub and Singtel charge similar fees for their SIM cards. Depending on the promotion on hand, you might get a few bucks off, but clearly the telcos don’t feel there’s an incentive to effectively offset this one-time, startup cost for users.

It’s little wonder that you don’t find many people tapping their phones at the MRT gates each day. You have to be a geek to want to do this.

Perhaps the telcos are betting on something easier, like Android Pay, Apple Pay or Samsung Pay, which the transport authorities are also trying out this year.

Backed by the millions of smartphones already out there, these technologies seem easier for users to adopt. Plus, you can link a credit card to them, so there is no stored value on the phone and you may not need a secure NFC SIM card to protect that.

The bad news, of course, is that you’re dealing with various global technology vendors and you’re held to whatever they roll out in the years ahead.

For a small market like Singapore, that’s often inevitable. While we want to be technology leaders, we cannot always be the pace setters without a large-enough user base, unlike in Japan.

The good news is that the mobile wallet technology is here now. After so many years of tests, it’s live and ready to use. The thing that needs to improve is user education. Plus, the costs have to come down.

There have to be more incentives for people to use these new payment methods if the country wants to go fully cashless. No, this doesn’t mean forcing them to do so by removing the cash top-up option at the stations, as the authorities plan to.

All these mobile wallets and cashless payment options have to go beyond the usual user base of geeky enthusiasts, who are willing to browse through long lists of FAQs.

To gain broad acceptance, they must be easier to use. And first, people have to know about them. Without that, the technology will end up a white elephant.

I’ve been doing this for nearly a year now (as soon as I got my Samsung S8 phone) and I love it! Together with Samsung Pay, I almost never need my wallet.

That’s cool. Yes, I think with more education, users will be more keen to try it out. It does offer more convenience – if you bother to get past the initial hurdles.