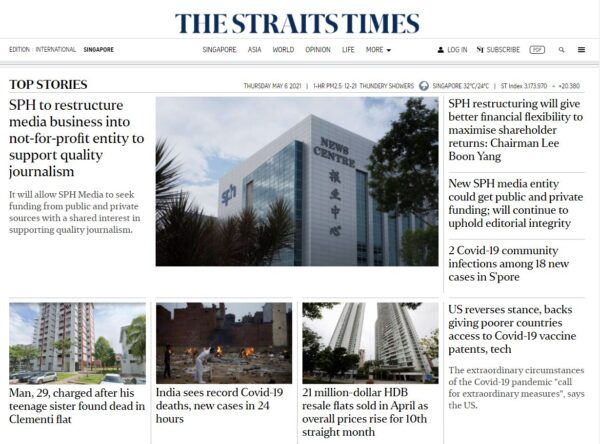

In a day of groundbreaking change for the Singapore media industry, you’d have thought the discussion would be about the future of journalism as Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) sought to turn its media unit into a not-for-profit entity.

Yet, there’s much online chatter about its chief executive seemingly losing his cool when asked about maintaining editorial independence.

At a media event, Ng Yat Chung said he took umbrage at questions about his company’s independence, according to a report in Today.

Telling reporters present that their own organisations also received substantial funding from various sources, he said SPH had never conceded to the needs of advertisers.

“The fact that you dare to question (the editorial independence) of SPH titles… I don’t believe even where you come from, you concede in doing your job,” he reportedly said.

Perhaps it’s the tone of the retort. Or perhaps those questions hit at something that has been staring at SPH for a while – the need to shore up its credibility in a competitive field.

The South China Morning Post (SCMP), for example, regularly reports on the biggest stories in Singapore, from the family feud involving the prime minister to the country’s Covid-19 response.

Often using a more critical lens to analyse the news, SCMP is winning readers who want an alternative view of things from the biggest local masthead, The Straits Times.

There are more competitors from afar, like The New York Times, Financial Times or The Guardian. But they are not so much competitors for eyeballs as they are alternative ways to run a newsroom in the digital era.

The difference between them and SPH is that they have managed to transform successfully, at least in recent years, to keep relevant with readers.

Just yesterday, the New York Times (NYT) announced an operating profit of US$51.7 million in the first quarter of 2021, up from US$27.3 million in the same period last year.

Higher digital-only subscription revenues and higher digital advertising revenues more than offset lower print advertising, print subscription and other revenues, it revealed.

Yes, a competent digital product is key. More importantly, credibility sells.

Like every newspaper, NYT had its troubles too when switching from print to digital. In the past few years, it also had to face off against an American president who regularly assaulted the independence of the media there.

Yet, it has emerged stronger, despite the pandemic and the industry’s structural disruptions.

The FT holds useful lessons too. It transitioned from a salmon-coloured broadsheet with zero digital subscribers in 2009 to winning over more than 1 million paying subscribers in 2019.

The Guardian, meanwhile, had 1 million subscribers by December 2020 as well, despite keeping its content open to all, unlike FT which walled up its articles for paying customers.

SPH, unfortunately, has seen its media revenues shrink in recent years despite various efforts at digital transformation. Staff have been laid off.

It’s not that SPH hasn’t tried. Indeed, it was early with its online efforts with AsiaOne, a Web portal bringing together the company’s various newspaper articles back in the late 1990s.

Listed on the stock exchange in 2000, just as the dot.com bubble was about to burst, it was delisted less than two years later.

Now, can the new SPH media unit, which operates separately as a not-for-profit, reinvent itself?

It’s interesting that the company listed The Guardian, which has been controlled by the Scott Trust since 1936, and the Tampa Bay Times in the United States, which is owned by the non-profit Poynter Institute, as examples of other non-profit media outlets.

But the big thing about these outlets is their credibility, which is only possible with their independence. Being a non-profit is just part of the equation.

If SPH’s proposed changes get approved by shareholders, the parent company shall not be subject to Singapore’s Newspaper and Printing Presses Act, according to the company. But what about the media unit?

For those unfamiliar, the legislation requires newspaper companies here to have “management” shares, each of which gives the holder the equivalent of 200 times the voting power of a regular share. The minister in charge has to approve persons who hold such shares.

If you’ve ever wondered why the media is what it is in Singapore, or groused that The Straits Times is sometimes too “pro-government”, know that the legislation in place gives the government significant, if indirect, control.

Now, government officials don’t tell the newsroom what to do every day, obviously. Many reporters in SPH put in an honest shift and frankly, deserve better. Others have gone on to international media outlets and done well, actually.

The Singapore government also doesn’t want the media to simply parrot what it says, but it does want the media to help explain its policies to citizens, which is fair enough.

But to do that, as anyone knows, you need credibility. In turn, you need reporters to be independent and trusted sources of information.

How will the new SPH media unit play this role? For starters, what it certainly needs is an independent board and competent leadership to build its credibility.

Print may be dead and the business models of old uprooted but news media that strive hard to be independent are still very much alive because they are valuable to their communities.

DISCLOSURE: The writer owns a small amount of shares in SPH.