In a journalism fellowship to China, India and the United States years before today’s fraught geopolitics, I was told by chip designers, semiconductor companies and their industry associations one similar message – the days of doing everything yourself were nearly over.

In 2007, the industry was undergoing profound change. China’s opening up to be the world’s factory meant almost every new electronic device was going to be made there.

India had thousands of expert engineers who had spent time in American electronics firms like the old Texas Instruments and were eager to start out with their own chip design companies. If only they could find someone to manufacture their chips.

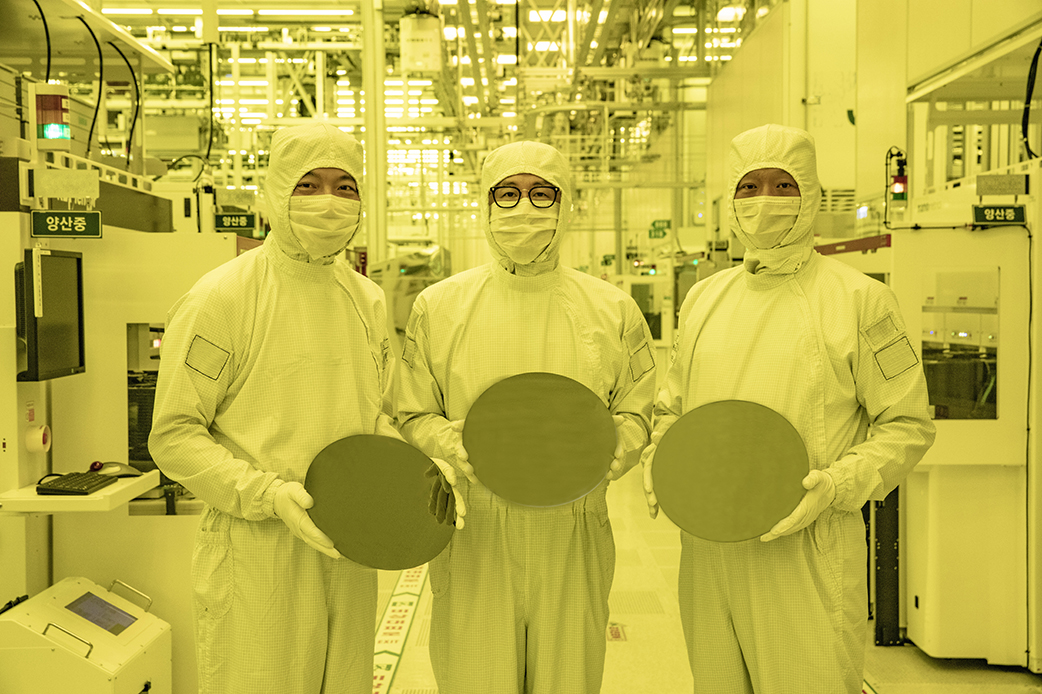

This was where chip foundries came in. These contract manufacturers took chip designs and manufactured them in bulk by investing in high-tech machines and processes that smaller chip design companies could not afford to.

And American technology firms saw the future clearly – they might all have to outsource the manufacture of chips overseas, to Asia, particularly Taiwan, which had an expertise in it, to be competitive.

In this post-Cold War world, globalisation and outsourcing were the bywords for success. If you could find a niche in this highly optimised, closely knit semiconductor supply chain, you could make a lot of money making the digital foundations for anything from phones to cameras.

Things are a little different today. Sure, the semiconductor industry is still making lots of money – exceeding US$600 billion in 2021 – but the fine balance it had achieved over the years is facing an uncertain future.

To the surprise of many in a “boring” sector that outsiders simplistically associate with people in bunny suits, it has become the centre of attention amid great-power politics in recent years.

The latest move came from US president Joe Biden today, as he signed a landmark Bill to provide US$52.7 billion in subsidies to boost the country’s semiconductor production and research.

Called a “once-in-a-generation investment in America”, the effort is aimed at bringing the manufacture of components critical to its economy and military back on home soil.

As Russia found out in its costly invasion of Ukraine this year, Western sanctions that limit the export of the semiconductors used to make, say, precision weapons, have badly hurt its war effort.

China is also ramping up its own expertise in this sector, after seeing Huawei being starved of the most advanced smartphone chips and losing its lead in the market.

The Chinese company’s difficulties have been well documented. A key reason is how the semiconductor sector has been set up over the past decade and a half.

In a bid to overcome inefficiencies, any overlap has been thoroughly consolidated. This means there usually are very few players doing the same thing in the complex supply chain that turns silicon into chips containing millions of transistors.

One important part of this chain – fabrication plants that manufacture the chips on a mass scale – has been the focus of late.

Though there are a number of them around, only two – TSMC in Taiwan and Samsung of Korea – have the know-how to make the latest generation of chips using a 3-nanometre process.

Even if you have the expertise to do so, it costs US$20 billion to build such a plant. This is just one “bottleneck” in a highly optimised sector with hardly any slack.

Notably, in 2001, there were 17 companies that could make the most advanced chips, according to Stanford, but today only TSMC and Samsung will be able to make that dream chip you have just designed.

Further down the chain, you’d also find that there are very few companies that design and make the machines that make these chips.

ASML in the Netherlands has been in the news as the main go-to outfit for anyone making a machine to make computer chips. It controls 90 per cent of the market for these lithography systems.

ASML works with Imec, a Belgian research outfit that produces breakthroughs in lithography, which “prints” a circuit design onto a substrate using highly sensitive equipment.

Without the expertise and innovation from these places, it is hard to design and produce a cutting-edge chip from the ground up. And if you have been noticing, many of these outfits are from the West or West-friendly places.

This is not to mention others in the supply chain, such as electronic design automation (EDA) tools from American companies like Cadence and Synopsys, which make the software needed to design a complex chip.

Plus, there are chip design companies, such as Arm from Britain, that license their designs as building blocks to build more advanced chips.

Apple’s groundbreaking M1 and M2 chips are based on Arm designs, as are most of today’s smartphone chips from Qualcomm and Samsung.

This is why China, which depends on semiconductors for its self-designed products as well as those that it makes for foreign manufacturers, has embarked on a well publicised effort to be self sufficient.

There was news recently that the country’s semiconductor firm SMIC could make 7-nanometre chips, apparently a breakthrough despite the Western restrictions.

That is still some way from the most advanced chips, however, and many experts you ask will say it is not that easy to vertically integrate a globally optimised supply chain.

The same problems will face the US, as it seeks to secure its own supply of advanced chips by making them on home soil. Some of its chip champions, such as Micron and Intel, run their own fabs to make their own chips, but this business is not an easy one.

AMD, a long-time rival PC chipmaker to Intel, will tell you this. Its founder Jerry Sanders once famously said “real men have fabs” in a retort to competitors outsourcing their manufacturing.

However, it too had to cast off its fabs in 2008 after struggling to maintain them. Since then, it has moved ahead of the game by outsourcing the manufacturing of its chips to third parties.

Designing more advanced chips to be made with new-generation manufacturing processes meant it could beat Intel at performance. It has also become a more valuable company than Intel.

So, departing from a well optimised supply chain carries risk. As governments seek to bring their semiconductor fabs and expertise home, they also might make them less competitive and more costly to run.

In a perfectly balanced semiconductor world, nobody does anything that doesn’t add value – they are quickly consolidated – so the next generation of chips will keep improving at breakneck pace to enable new uses.

This fine balance is also why any small disruption will set back supply drastically. The pandemic, a war in Europe and geopolitical tensions between the two largest economies have not helped.

The chip shortage is why you have not been able to buy a Playstation 5 (without paying a scalper) and why the car you just ordered doesn’t come with a head-up display.

The issue will get more acute in the years ahead, as every other smart device looks to have a logic or memory chip inside, from a self driving car to a military drone.

Now imagine if the semiconductor sector gets disrupted further in the short term or de-optimised over a longer period. Or worse, if TSMC, situated on an island that China claims and the US promises to help defend, becomes a flashpoint for a larger conflict.

Today’s technology Cold War is a long way from the perfectly tuned, optimally efficient conditions that many had expected the semiconductor sector to enjoy more than a decade ago. The view from the clean room has changed.