Imagine using your phone to pay for your wantan mee at a hawker stall, only to find that you can’t log in to your bank account in Singapore’s cashless society.

After scrambling for some dollar notes, you later check again and realise that the bank’s mobile app had blocked you from logging in because your phone contained several apps that it had deemed to be security risks.

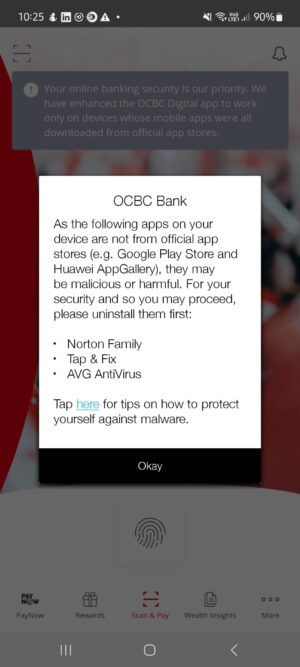

Unless you uninstall these apps from your phone, you won’t be able to use mobile banking to pay for items, transfer money or simply check your account balance on the go.

Faced with such a surprise in the past week, OCBC customers are rightly upset about how their bank has gone about shoring up cyber defences against scams.

After having to cough up millions of dollars to about 470 scam victims early last year, OCBC isn’t going to go light on security, you’d imagine.

Now, the bank seems to have gone about beefing up its efforts to keep out scammers and hackers in a way that customers say is too high-handed.

For instance, could OCBC have told customers beforehand that an update to their mobile app over a Saturday would trigger a lockout from their bank accounts?

For clarity, the bank has since come out to say that it’s not blocking all apps downloaded from third-party app stores or those that you side-load or install from a separately downloaded APK installation file.

It only looks out for ones that may be “high-risk” and flags them for users to assess, OCBC has said.

Of course, there’s a limit to what a user can do after that – he can either delete the offending apps or stop using the OCBC banking app altogether. In anger, many customers have taken to social media to say they’d close their bank accounts.

There are multiple issues here. One is the question of whether a bank app should scan your phone and tell you to uninstall some apps before you can log in to the bank.

Though it seems controversial, OCBC isn’t the first bank to set such conditions for using its mobile app to log in.

Over the years, other banks in Singapore have also restricted access to users who “root” their phones or run third-party firmware or operating systems that are not from the manufacturer. Again, the idea is reducing risk.

Don’t forget that recent incidents of people losing large amounts of money, including their retirement savings from CPF accounts, often start with the download of malicious apps that gain access to their phones.

That said, OCBC’s approach needs to be clearly explained to consumers. Even though no content is accessed, according to OCBC, how many users would install a banking app expecting it to look through their phone for high-risk apps? Did the users even consent to that?

OCBC’s intentions may be good, because, yes, you should avoid downloading apps from third-party app stores and unverified sources.

Of course, apps from Google’s Play store also have been known to contain malware. Some, for example, start off legit but over time add malicious code that take advantage of the access that a user has given previously.

However, Google’s regular checks do make the official store a lot less risky to download apps from. For most users, this is where you should get your apps from.

The second, larger issue is how OCBC has gone about this exercise. Most concerning is why some seemingly legitimate apps, including security apps downloaded from the Google store, are also flagged by the bank.

Worryingly, users on its Facebook page have complained about some popular apps downloaded from official channels being flagged.

Microsoft Authenticator, for example, is needed to log in to corporate or business accounts, while Norton security ironically is meant to protect a phone from cyberattacks. How can the bank expect users to uninstall these apps?

OCBC has to quickly resolve these issues for users who have basically followed its rules and yet are still locked out and greatly inconvenienced. Otherwise, it risks losing customers altogether.

Indeed, that is the onerous task that the bank has before it. If it wants to go the distance to help customers better secure their phones, it best get things right.

Rolling out cyber defences that flag too many false positives ends up cutting customers off, possibly for good. Basically, it would have DDoS’d or denied its customers a critical digital service.