Situated opposite a row of public flats and surrounded by newer factory buildings around it, the Micron Technology assembly facility in Bendemeer Road in Singapore is almost hidden in plain view.

On the outside, the building looks its age – it’s been in the same spot, plus some extensions, since the 1970s, when it started life as a semiconductor manufacturing facility for Texas Instruments (TI), which was bought by Micron in 1998.

Inside, the building has undergone upgrade after upgrade over the years to boost the facility’s manufacturing capabilities. Today, it is used for the assembly of NAND products, such as the solid state drives used in phones, cars and data centres across the world.

While the shell of the building, known as the Micron Singapore Bendemeer (MSB) site to employees, comes from an era before PCs arrived in homes, its several manufacturing floors and clean rooms have undergone high levels of automation to make the advanced storage modules that enable today’s smart devices.

The building is a testament to the strength of the partnership that Singapore has forged with high-tech manufacturing firms such as Micron, despite competition from larger markets and lower-cost countries such as China and Malaysia.

It’s also a story of innovation, by making use of the limited space optimally and upgrading the facility even as it continues to be a live production floor over the years.

At a time when the focus is on the latest cutting-edge chips made by the most advanced semiconductor firms in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, this site in central Singapore is a reminder that the Republic remains a crucial cog in the global high-tech manufacturing industry.

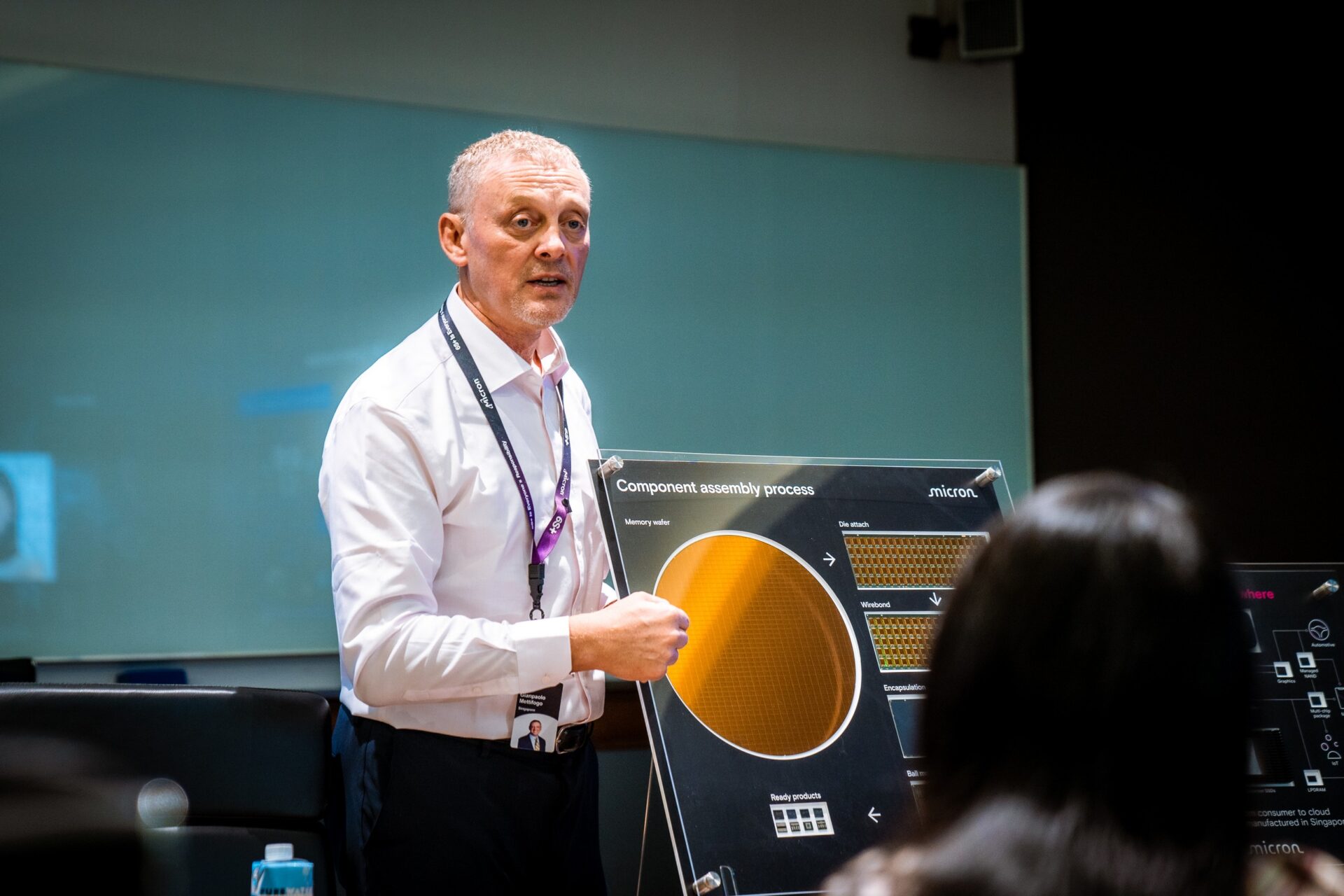

While the Bendemeer site receives wafers and other electronic components made at other Micron sites to assemble here, the high level of automation here means it can efficiently push out the latest flash memory components and devices, said Gianpaolo Mettifogo, Micron Singapore’s vice-president of assembly and test.

The upgrades over the years have enabled this Singapore facility to be a relevant part of the demanding global semiconductor supply chain, he noted.

For example, the low ceiling in the building meant that the company had had to adapt the transport system used by the many box-sized automated vehicles that zip through the facility to carry semiconductor components across the factory floor.

Instead of using the same system in its newer, larger facilities in the north of Singapore, which makes sophisticated flash memory chips, Micron engineers found that a system similar to one used by Light Rail System (LRT) trains in the country would work better in Bendemeer.

By automating many manual tasks, this system enables the facility to run 24/7 with minimal human input. Usually, only when an expected issue arises does an operator in the clean room need to intervene.

Staffers at the facility, who hosted Singapore media in November, pointed to the efforts to not only improve the manufacturing capabilities but also the staff facilities. On the rooftop are a basketball court, a gym and barbecue pits, next to a canteen that sports a Starbucks outlet.

They are additional examples of how this old Micron building and indeed Singapore itself are overcoming physical limits to find a niche in the global semiconductor sector.

It fits in nicely with the newer larger plants in the north of Singapore, which make the sophisticated multi-layered NAND chips used by the Bendemeer site to make flash memory modules.

Across the various facilities, the Republic is responsible for almost all the NAND memory produced by Micron, accounting for US$2.1 billion or about 30 per cent of its revenue in a quarter.

That said, some of the most advanced and “hottest” chips of the moment – the high-bandwidth memory (HBM) chips used for AI today – are made elsewhere at the moment.

Micron is expanding its facility in Taiwan for this, while also being reportedly keen on American, Japanese and Malaysian plants to boost HBM production.

Earlier this month, Micron said that it plans to invest in HBM manufacturing in Singapore, with support from the government. Starting in 2027, this would boost its advanced packaging capabilities in the country, meeting the growing demand from AI uses.

In more than 20 years in Singapore, Micron has already invested more than US$30 billion in the country and hires close to 9,000 people.

Altogether, the semiconductor sector employs about 35,000 people and accounts for almost 20 per cent of the country’s manufacturing output, reported CNA.

So, it’s unsurprising that Singapore is opening up 11 per cent more land to attract semiconductor firms to the country, promising customised roads and new water piping.

Such efforts will be key to tapping into a red hot opportunity opened up by the rise of AI and ongoing digitalisation from cars to home appliances.

Plus, to avoid losing out as a key innovation node, as the global race to make the most advanced chips heats up even more in the years ahead.

In years to come, it will be interesting to see what role Micron’s decades-old facility and Singapore will be able to play with even newer semiconductor advances.

UPDATE: The story was updated at 27/12/2024, 7:45pm to reflect Micron’s latest comments on investing in HBM manufacturing in Singapore.